When I started my first “Legend of Zelda” title years ago, I remember my confusion when I learned that the character as whom I was playing was not named “Zelda,” but that I could actually name him whatever I wanted, and that his canonical name was “Link.” The game purported not to be about any legend of Link; rather, it was centered upon a yet-unknown character known as Zelda.

In a game like “Ocarina of Time,” the player meets Zelda fairly quickly, and is primed by the title to recognize her significance in the game: she is the major nexus of Link’s relationship to good and evil; she is the target of Ganondorf’s conquest; she is the holder of the Triforce of Wisdom. Much can be said about the role of Zelda in the games’ canon and why the story arc is ultimately defined in terms of her legend; for our current purposes, however, this is only background.

This is “background” in the strictest sense of the term because what I wish to explore presently is this: in the game entitled “Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask,” Zelda does not exist. Aside from a flashback sequence in which Link remembers the Song of Time, which Zelda ostensibly taught him before he left Hyrule, there is not even a mention of her within the world of Termina, let alone any encounters with her. Even if one grants that the moniker of the game must include her name in order to identify it with the greater series, one must still account for the fact that the central figure of the greater series has been very apparently omitted from this specific title. It is this anomaly and its effects that I chart in this post — first in its global implications, and then in how it locally manifests in the characters of Termina.

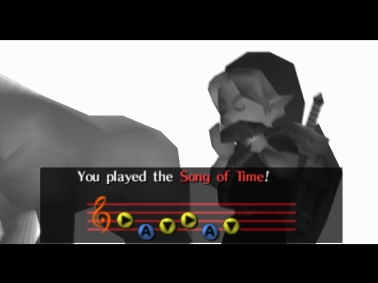

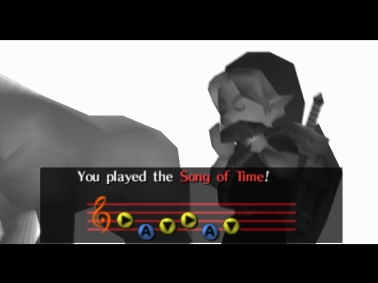

As a way into Zelda’s relation to “Majora,” consider first the one instance where she does make an appearance: when Link remembers the Song of Time (1:35 in the video). Upon reacquiring the Ocarina of Time from Skull Kid, Link is overtaken by a vivid flashback of when he was leaving Hyrule, and a young Princess Zelda said goodbye to him, entrusting him with the Ocarina of Time and teaching him the Song of Time; thus, by experiencing the flashback, the Link who presently faces Skull Kid atop Clock Town’s clock tower remembers the song, and is able to use it to reset time for the first time in the course of the game.

The significance of this encounter hinges on what it means to “remember.” Consider how Zelda, in the flashback, describes the Song of Time: “This song,” she says to Link as she plays it, “reminds me of us.” Just before playing the song for him, she remarks that “even though it was only a short time, I feel like I’ve known you forever.” To the player who has the background of “Ocarina of Time,” this remark is especially important: for though Zelda could not possibly remember the events of “Ocarina of Time,” the game is nonetheless evidence of a life that she and Link spent together. The plot of “Ocarina” revolves around Link rewriting the game’s timeline in order to prevent the conquest of Hyrule by Ganondorf: at the end of the game, Link seals Ganondorf outside of time with the help of the Seven Sages, establishing a new continuity in which Link and Zelda never embarked on a seven-year quest against the Great King of Evil. The game closed with a look into where this new timeline might go, with a young Link encountering Zelda at Hyrule Castle.

The tension between the timeline-that-never-was, as it were, and the timeline which emerged out of Link’s quest, is compounded by the role played by the Song of Time. In “Ocarina,” Link learns the Song of Time through a message sent to him by Zelda after Ganondorf has kidnapped her; it is this song that allows Link to unseal the Door of Time, triggering his seven-year stasis and leading to Ganondorf’s conquest of Hyrule. Thus there exists no prima facie reason in the timeline as resolved post-“Ocarina” why Zelda would be reminded of Link and herself by the Song of Time. This fact, combined with Zelda’s remark that she feels as though she has known Link forever, suggests to us that timelines within “Zelda” have something of a bleeding effect.

We must be precise with what we mean by this. As I mentioned above, what my analysis hinges on here is the conception of “memory.” Zelda in Link’s flashback appears to vaguely conceive of events outside of her own timeline, experiencing what we might call a “temporal afterimage.” By “temporal afterimage,” I mean mental remnants or representations of alternate timelines that necessarily precede the timeline in which one actually exists. So to precisely define the bleeding effect that I am describing, we may say that it refers to “the tendency of intersecting timelines to generate temporal afterimages.” This definition is useful because, beyond the scope of Zelda, we see the bleeding effect running rampant in “Majora”: in fact, it is a parsimonious metaphysical model for explaining why certain objects, like masks, remain with Link when he resets time. By this model, each usage of the Song of Time in Termina instantiates a new timeline, and masks &co obtain in the new timeline as temporal afterimages, brought into the reality of the new timeline by Link’s mind, which serves as the node of intersection between old and new timeline.

When I treat time in more depth later in the blog, this will be examined more closely; at present I want to return to Zelda, the subject of this post. What I have aimed to establish in the preceding argument is that memory within the “Zelda” universe is at least sometimes the result of the bleeding effect. I have argued this in order to prove that Zelda does not exist in “Majora’s Mask,” or in Termina. To see this, recall the argument that I made at the end of an earlier post, that the Link who exists within Termina is not the canonical Hero of Time; reading that argument, one might rightly wonder about what possible mechanism could be employed by the game to convince the player that Link is the Hero of Time, when, in fact, he is not. The bleeding effect offers us just such a mechanism: we think during Link’s flashback that he is recalling the aftermath of “Ocarina,” because those events took place outside of the scope of the game and we have no point of reference to verify or deny them; yet our examination suggests that, contrary to the intuition imposed upon us by the game, the Link of Termina is actually experiencing a temporal afterimage of the Hero of Time. If we accept this argument, it follows that not only is Zelda not existent within the world of Termina; she has never truly existed for the Link of “Majora,” except as a temporal afterimage.

Another result of this theory is that it adds explanatory strength to the metaethical nihilism that I defended as a thesis of “Majora” in an earlier post. I observed that the game mechanic of the Fierce Deity’s Mask implies that moral truths do not obtain in Termina. We also see in other “Zelda” titles — particularly in “Ocarina” — that Zelda serves as a moral compass for Link. It is she who initially sets Link on the path against Ganondorf, and who, in the guise of Sheik, directs Link to each of the Sages whose help he needs to defeat the Great King of Evil. In the same vein, recall that in “Ocarina” (and generally within canon), Link is the bearer of the Triforce of Courage, whereas Zelda bears the Triforce of Wisdom. Thus it makes theoretic sense that Zelda would be the one who tempers Link’s courage through the application of wisdom in the form of morality; and, in a world without Zelda, with Link never having met Zelda, it makes theoretic sense that morality does not fundamentally obtain.

Return, then, to Link’s flashback in which he “remembers” the Song of Time: what significance does that particular temporal afterimage have in relation to the rest of the game’s universe? There are many possible explanations; below, I assess what I take to be the three that are most compelling.

1. Zelda is a deus ex machina. On the most basic reading, Link needs to remember Zelda at that moment because otherwise the moon will oblierate Termina. Thus he needs access to the Song of Time in order to negotiate the timeline of Termina and actually proceed on his quest to save it.

Of course, this account is not without wrinkles. I have already pointed out that Link ultimately cannot save Termina, because Termina is defined by its apocalyptic fate. So the use of a deus ex machina would not actually cohere as a device to save the world, but only as a device to grant Link limited agency. A noteworthy facet of this account is that it creates a sense of narrative irony when the game is viewed in dialogue with “Ocarina”: in “Ocarina,” Link can only traverse time from one fixed-point to one other fixed-point seven years apart; yet, given this limited metaphysical agency, he is able to succeed in his quest to negate the Great King of Evil; contrariwise in “Majora,” Link has much more liberty in the manipulation of time, yet he cannot ultimately succeed in freeing Termina from its fate.

2. The Ocarina of Time transcends all time. We usually describe the Ocarina of Time as an object that facilitates travel along a single timeline; yet given this ability, it is not altogether implausible that the Ocarina also resonates between timelines to some extent. Under this interpretation, it would make sense that its bearers, Zelda and Link, would experience temporal afterimages. The major complaint here is the lack of mechanics for explaining the Ocarina’s dual functionality. How is it able to manifest in multiple distinct timelines, and what is happening at the intersection of metaphysics and epistemology that allows its bearer to actively travel a single timeline, but also to merely glimpse the remnants of other timelines?

And in the bizarre world of Termina, we would see the intersection of these capacities, because Link actually does travel through many distinct timelines of Termina by using the Song of Time. This could easily be a unique function of Termina’s metaphysics — for example, the distinct timelines of Termina could all exist as members of one larger “set” of timelines, on which the Ocarina acts as though it were one single timeline — but such an account seems clunky without a much more involved account of what the Ocarina exactly is, independently of Termina or Hyrule.

3. The entropy of the universe is ultimately pernicious. First, I must take a moment to parse what I mean. “Entropy,” in particular, need not be interpreted as a physicist’s strict account of the concept; I am happy to gloss it as “the increasing disorder of the universe as time progresses.” What I have in mind as this increasing disorder is the proliferation of timelines: as “Ocarina” and “Majora” progress, timelines manifest, are played out, and fall away, effectively abandoned for the sake of new ones. Time branches as Ganondorf is sealed away; time dies and is reborn every time Link resets Termina; and all along the way, all that remains as evidence of the journey is the formation of the relics which we have been calling temporal afterimages, which amount to little more than distant memory — or, indeed, than legend. So we are left with half-recollected stories which never truly happened, but which present themselves to us as artifacts of truth. It is this connection of increasingly myriad timelines through temporal afterimages that grounds the increasing chaos of “Zelda” as the story progresses, and the particular instance of Link “remembering” the Song of Time demonstrates the pernicious nature of this chaos.

In the moment when Time itself is at its end, Link experiences an epistemic shift which connects him through a temporal afterimage to the Hero of Time, and the Song of Time instantiates itself in the alien world of Termina. In so doing, it allows Link to traverse Termina with the hope that, under the guidance of Zelda, he can save it from the threat of annihilation by Skull Kid. Yet Termina is an irreducibly doomed world, and that hope is ultimately parasitic on Termina’s pessimistic fate. All that Link effects is the proliferation of more timelines, all of which are ultimately doomed to termination, just as the world’s name suggests. So the false memory of Zelda ultimately promotes the chaos of a fatalistic universe, disguised, by the protagonist’s hope, as something that can be saved.

I think that all three of these theories have advantages and drawbacks; strict canonists will probably be most satisfied by Explanation 2, whereas I am most tempted by Explanation 3. I do not believe that this account is as speculative as it may seem as first glance: “Zelda” as a series is unabashed in its usage of multiple timelines and nonlinearity; I think that embedded as a natural extension of the account which I have offered thus far is the fact that Termina can be viewed as the ultimate corruption and decay of that multi-universal structure.

In the post so far, I have discussed the consequences of the princess who is not present in “Majora”; yet this analysis would be incomplete without service to the “princesses” who are present in the game. Before concluding, I want to briefly consider whom I see as a Zelda-analogue in each sector of Termina, and how they collectively tell a story of the Zelda-concept relative to the world of Termina.

In the first section of the game — the swamp — Link must undertake a quest to rid the swamp of poison and rescue the Deku Princess, who is imprisoned within the temple where the first Giant is sealed. This quest in many ways resembles the classic “rescue the princess” quest, but is heavily parodied: the princess’s rescue is advocated for by a monkey, and Link must transport the uppity princess back to her father by literally stuffing her into an empty bottle. In the very first stages of the game, then, we see a Zelda analogue that has been satirized into the realm of the absurd.

When Link moves on to the mountains, he encounters the son of the Goron Tribe’s Elder — a prince, as it were — who is little more than an infant, crying for his father who has yet to return from a quest outside of the village. Link must soothe him by finding his father, and playing him a lullaby which the Elder half-remembers, and which the child completes. This quest-driving Zelda analogue is even less mature than the young Zelda whom we encounter in “Ocarina,” and exacerbates the image of a royal heir as one whose problems demand solving purely by virtue of their inheritance.

Link then arrives at the Great Bay to find Lulu, a girl who is the lead singer of the Zora’s band, The Indigo-Go‘s. Before the events of “Majora,” she lost her voice and laid seven eggs, which Link eventually reclaims from pirates — only to find that the eggs hatch into Zora children who form the notes of a melody, which Link must play to Lulu to restore her voice. In singing the song, she summons the enormous turtle who is the guardian of the temple to which Link must travel in order to liberate the third Giant, purifying the Great Bay’s tumultuous, clouded waters. Though Lulu does have a tragic backstory with the fallen hero Mikau, it is difficult to see her as more than a plot device: she is rendered speechless, and her children are literally designed to grant Link passage to the Great Bay Temple, restoring their mother’s voice in the process. So while she is certainly a character with pathos, Lulu is also emblematic of the princess who is reduced to at most a plot device and at least a deus ex machina, existing only to effect progress in the hero’s journey.

One could plausibly argue that no princess analogue exists in the stark Ikana Canyon, just as Link does not acquire a new transformation mask in the canyon; yet I believe that the little girl named Pamela who lives in a music box house with her cursed father is in fact another analogue. Pamela is a little girl whose father moved them to Ikana to research ghosts and spirits, but who accidentally transforms himself into a Gibdo — a type of mummy-like spirit — in the course of his research. This forces Pamela to lock him in a closet in their basement, as Gibdos circle their home in a desire to claim her father as one of their own. In my eyes, Pamela is the exemplar of a princess trope that is desperate to assert a measure of control and agency that ultimately does not belong to her. She is powerless to stop the Gibdos, and Link, the only one who can heal her father, must actually sneak past Pamela in order to enter their home — by being so paranoid and fearful for the sake of her father, she would keep out the one person who could save him. Thus Pamela is the tragic princess who wrongly believes she can save herself, and who, by virtue of that very fact, is most in need of saving.

I have already mentioned Clock Town’s princess analogue, Anju, once before in my discussion of the value of sidequests in “Majora”; I am loath to mention her in passing again because the story of Anju and Kafei demands treatment in a post all its own, and yet Anju is irrefutably the fifth princess analogue. Anju is the innkeeper in Clock Town, engaged to Kafei; but Skull Kid transformed Kafei into a child a month prior to the wedding, and a thief (Sakon) stole the mask that Kafei was to exchange with Anju at their wedding ceremony. This caused Kafei to go into hiding in an attempt to reclaim his mask; yet Anju was left knowing only that Kafei ran away, and fears that he might have done so because of her, or (as her mother suggests to her) to seek a better partner in the owner of Romani Ranch. Anju is trapped in the most tragic, yet most existentially significant situation of all: hers is the only fate of the five mentioned characters in which Link does not have to intercede in some way. If Link does not intercede, then Anju will be left waiting at the altar when the moon falls; yet if he does intercede, then she and Kafei will be married under the falling moon, only with the goal of perishing together (for, as previously mentioned, Link barely has time to stop the moon’s descent if he sees his sidequest through to the end, and it seems that Anju and Kafei would prefer to perish than be saved). Anju, then, is the princess as the tragic lover: the only difference in her fate is whether or not she will know in the end the fact that Kafei loves her and wants, literally and figuratively, to die with her.

What emerges from this world without Zelda is a fivefold princess cycle: the comically absurd, the childishly immature, the silenced plot device, the self-defeating victim, and the doomed lover. I believe that it is the absence of moral valence — which, as I have defended above, is due in large part to the absence of Zelda — that allows us to perceive these five different forms of the princess. The reason is because the absence of a moral imperative transforms the concept of the princess from that of “the one who must be saved” to that of “one who could be saved.” In the review, though some of these characters must be “saved” by Link in one three-day cycle, none must be saved in order to complete his quest in the way that saving Zelda is inextricably bound up with defeating Ganondorf. This allows each character to be uniquely flawed in the ways described above, because the paradigm of goodness in the game does not depend on them. Could we conceive of Zelda as flawed? Maybe, but my intuition is that such a critique would reduce to a critique of morality, because she, as the manifestation of Wisdom, exists differently than any of these existentially doomed princesses.

So what comes from a “Legend of Zelda” without Zelda? We see the picture of a universe that, on the most essential spatiotemporal level, is in a state of decay; yet at the same time, we see a universe that uniquely affords a depiction of humanity that would otherwise be eclipsed by morality inhering to the one who must be saved. The courageous hero is left without direction, yet it is by virtue of lacking direction that he is able to see the plights of those around him as human conditions, rather than as canonically good, evil, or neutral.