-by Laila Carter, Featured Author. The following article is based on Laila’s portion of With a Terrible Fate’s horror panel at PAX Australia 2016.

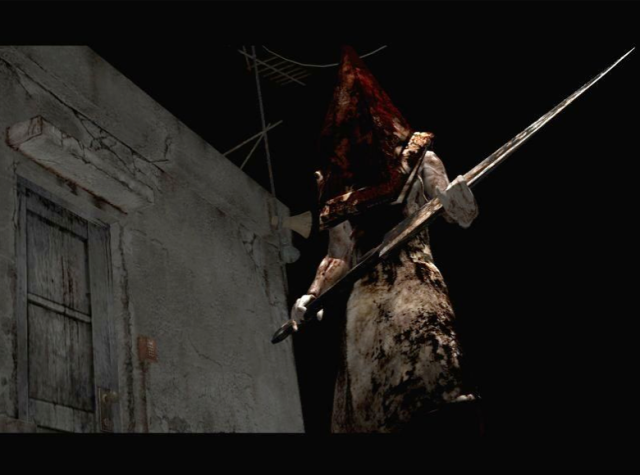

Horror is always an interesting genre: it subverts all the norms that we are used to, goes against human nature, and forces us to confront our own fears. When video games embrace horror, they enable players to willingly embark on a journey that thrives off of dread, thrills, the grotesque, the abnormal, and the contrary. What I want to explore is the storytelling elements behind this, and how the horror genre has transversed different media, from the ancient myths all the way down to present-day media. Storytelling tropes come together in gaming in a fascinating way, creating the fundamental aspect of the horror gaming genre: something that I term “Daemonic Warped Space.” Various mythological elements correlate to various aspects of this idea: specifically to the warped, to the daemonic, and to the combination of the two. In the paper, I will explore how this is the case, demonstrating how ancient and modern mythological tropes can produce horror atmosphere in the present-day storytelling of video games.

Mythological Roots: Horror Tropes

In ancient mythology, the first stories ever told, certain events or occurrences appear in several cultures, thus establishing themselves as common myth anecdotes. Whether these elements were shared between cultures or came about separately in isolation, these anecdotes are widely recognized and still used to this day. Here, we will examine three of these anecdotes in order to understand how they form the atmosphere of the horror genre.

One of the most prominent motifs in almost all mythologies is the descent to the underworld. A hero must embark down into the abyss, into the land of the dead to encounter its mysteries and overcome some obstacle that is keeping her from progressing. The Underworld is the most famous type of “Otherworld” – a supernatural realm of spirits, of the soul. It is a realm opposite to reality, one that makes regular mortals question their judgment, sanity, and existence. Most of the time, the Underworld is portrayed in a religious light since the afterlife is one of the greatest mysteries in all faiths. The Underworld can be Heaven, Hell, or Purgatory in the middle (like in Dante’s The Divine Comedy); it can be Limbo, the Spirit World, the Realm of Shadows, or it can be Hades in Greek mythology. But it doesn’t have to be religious: the Underworld is simply a place of no return, where the spirits of those forgotten tend to wander; if characters ever do escape, they come back up as changed people (and if they don’t escape, then the story is badly written). It is Frodo’s journey into the horrid land of Mordor, where the land is covered in ash, fire, and brutality; it is Limbo – the deepest layer of dreams – in the movie Inception; it is Harry Potter’s literal death and meeting with Dumbledore one last time. The Underworld may appear very differently in each medium, but each place has one thing in common: the realm serves as a place of spiritual undertaking, forcing the hero to deal with internal struggles and psychological roadblocks, whether those be identity crises, relationship issues, or lack of faith in others or oneself. As Clyde W. Ford says:

“Mythological journeys of descent into the world of the dead are symbolic of movement from the light world of ordinary reality to the dark world of the unconscious; there, just as when we fall asleep, we die to the world of wakeful consciousness and awake to the marvelous world of evanescent forms and symbols within. The challenge met by those who successfully travel these corridors of the psyche is to claim some boon or gift from this inner realm: an insight or revelation that will release the energies pent up in the labyrinths of personal and social crises; the marker of a new direction that offers reinvigoration where old ways have grown stale” (Ford, 20).

Once you enter the Underworld, it is very hard to escape. Successful characters learn to look within themselves for the way out of this haunting, confusing, and dreaded place. The hero’s descent, then, is not only to uncover whatever secret she needs to in order to progress in her physical quest, but also to overcome her fears and the crisis of mortality. She must accept who she is, including her faults, yet also realize her potential for growth—that it is not her time yet to stay in the land of the dead, but rather to find meaning in the descent as a way to challenge her current mindset and change it for the better. The journey to the Underworld helps the character cross the threshold into a “personal land of the dead…dying one’s former self so that a new self may be born in its stead” (Ford, 26). The character must confront the personal hell within herself before she can save the day. This does not necessarily mean defying death outright (though sometimes it does), but more of accepting death as a possibility. Characters learn to let themselves change in order to succeed in the normal world, whether they initially like it or not.

The descent to the Underworld is such a universal theme that is appears in almost every single mythology that exists: heroes rescuing (or attempting to rescue) their loved ones from death, immortals dying and becoming gods of the Underworld, or demigods trying to prove their resistance to death and courage. A famous example of the descent to the Underworld lies in the Odyssey. Odysseus must travel down to Hades in order to figure out how to get back home and restore his life. He meets all the fallen heroes of the Trojan War, as well as his late mother; from them, he learns to be a bit wiser, and to take a good look at what it means to be a (Greek) “hero.” Was the glory from the Trojan War really worth it? Does acquiring riches and killing all those people amount to such glory? Odysseus takes these questions to heart, and because of this, he is able to approach the problems at home with a new perspective, enabling him to win the “glory” of his home with tactics different from the Trojan War (except at the very end, but that’s always controversial). The Underworld and the meeting of the dead help Odysseus succeed in completing his goal of returning home and protecting his family. He has to overcome inner struggles and change his old self into a different man before he can leave to continue on his quest.

The second mythological trope of horror is hard to explain, given its nature. The Unspeakable “It” is a presence that permeates throughout the entire setting, invading all space with its terrible presence. This entity is usually never directly seen, but instead felt: the character is overcome with an inexplicable sense of dread as she feels something on her skin, something watching her every move—yet she cannot say what that something is. The Unspeakable “It” is an amorphous being contaminates the very air you breathe and surrounds you with its unsetting power. It has no shape or boundary, and it tends to make up its own rules as it grows into something overwhelming. There is no true escape from this creature: there is only unwilling acceptance, complete assimilation, or mad obsession.

The Unspeakable “It” appears in all forms of storytelling, though some incarnations are much subtler than others. In mythology, this creature can be a force of evil that constantly tries to consume the world—for example, the chaos god Apep from Egyptian mythology. It can also be a being who exists throughout the whole world and is not constrained to one specific place, like Gaea from Greek mythology. Many times, the Unspeakable “It” is simply “The Darkness” or “Chaos” with a capital ‘C’, as nothing else can really describe such forces. They just exist and usually try to thwart the heroes of the story. The most famous portrayal of this mysterious entity, however, comes from H.P. Lovecraft’s stories. Lovecraftian horror appears at the very beginning of the story and never leaves: it haunts the narrative to the very end, even if the characters somehow “kill” it (spoiler: Lovecraftian monsters never truly die. Their existence is permanent throughout the world). These monsters are made of a conglomerate of pieces, from tentacles to eyeballs, from disjointed arms and legs to inhuman mouths, from ordinary animals to creatures never seen before by a human.[1] These monsters can be unimaginable, as Lovecraftian himself can barely describe the creatures in his stories – they do not fit into a coherent description that humans would comprehend. For example: “It would be trite and not wholly accurate to say that no human pen could describe it, but one may properly say that it could not be vividly visualised by anyone whose ideas of aspect and contour are too closely bound up with the common life-forms of this planet and of the three known dimensions” (“The Dunwich Horror”). Most importantly, Lovecraftian horrors are ancient, huge, and everywhere. When describing his creature Yogo-Sothoth, Lovecraft states that it “was an All-in-One and One-in-All of limitless being and self—not merely a thing of one Space-Time continuum, but allied to the ultimate animating essence of existence’s whole unbounded sweep—the last, utter sweep which has no confines and which outreaches fancy and mathematics alike” (“Through the Gates of the Silver Key”). Lovecraft’s horror features creatures of unimaginable amalgamation and limitless possibility, threatening the entire earth and space as we know it.

Like Lovecraft’s monsters, the Unspeakable “It” is a “kind of force that doesn’t belong in our part of space; a kind of force that acts and grows and shapes itself by other laws than those of our sort of Nature” (“The Dunwich Horror”). It is an entity that invades our world like a parasite, consuming and overtaking everything in its virus-like corruption. The best thing to do it get rid of it as quickly as possible; however, you can never truly destroy the horror that is the Unspeakable “It,” because once it’s here, it is here to stay.

The last mythological story element we will consider is the Greek myth of the Minotaur and the Labyrinth. Blaming Athenians for the death of his son, King Minos of Crete required seven young men and seven young women from Athens to feed to his Minotaur—an abominable half-man, half-bull—as payment. After the second round of sacrifices, Theseus, the son of the King of Athens, decides to go as as one of the young men in order to kill the horrible beast and end the sacrifices. Unfortunately, the Minotaur resides in a labyrinth created by the genius inventor Daedalus, and escaping from its confusing halls is impossible. Luckily for him, Theseus has the help of Princess Ariadne, Minos’s daughter, who gives him string so that he can retrace his steps to escape the labyrinth. Theseus navigates the complex maze, kills the Minotaur, and becomes a legendary hero.

The Journey to the Underworld and the Unspeakable “It” trope have features of obvious relevance to the horror genre, but The Minotaur and the Labyrinth might instead seem like a very specific, heroic story. I argue that the monster-living-within-a-hostile-environment narrative is one of the main elements of horror, one that makes a story enticing and tense. The Minotaur knows the layout of the Labyrinth, having lived there all its life, while Theseus does not. He, and others before him, had a great disadvantage as they had to navigate an environment that was foreign, confusing, and treacherous. The Athenians did not know the “puzzle” of the Labyrinth, whereas the Minotaur could easily find its way around. Theseus had to figure out a trick to solving the puzzle (i.e. using the string) in order to survive. However, unlike Theseus, many characters have a hard time finding “string” in their world’s labyrinth. These characters did not have outside help, and instead had to make their own string—sometimes on the spot, and other times through dangerous games of trial and error. All the while, they must escape from a terrifying force that wishes to destroy them. The danger can take place in a literal maze, like in the story The Maze Runner (which is the entire plot of the book). For a more figurative type of labyrinth in the same genre, The Hunger Games presents an open world of survival; there is no “maze” per se, but the setting remains hostile and foreign to Katniss, filled with murderous enemies and lacking any plausible means of escape.

For a more concrete example of the Minotaur and Labyrinth trope, in Neil Gaiman’s fiction book Coraline, Coraline must somehow find a way out of a distorted world that mirrors her own small neighborhood: a world that is controlled by the Other Mother, a grotesque, button-eyed figure who wishes to consume the girl’s soul. Coraline must traverse the twisted and changing hallways of her Other house, encountering decaying forms of her Other Father and neighbors, and saving her parents from the dark distortions of space and shadows. The Other Mother created the eerie version of the house and watches Coraline at all times—she knows the “labyrinth” that Coraline has to navigate, and is fully aware of the girl’s every move, putting Coraline at a severe disadvantage. Coraline also has no string at the start of the perilous journey, no way of knowing how to defeat the Other Mother and escape her realm; over time, however, she manages to overcome her fears, find a few allies, and collect resources to fight against the Other Mother and escape.

The Minotaur and Labyrinth story element, when used in horror, creates an atmosphere that keeps the reader/audience on the edge of their seats. The monster and the setting have combined into one force that the heroes must overcome in order to succeed, even though the monster has the advantage of knowing where it is in terms of space and time, while the heroes do not.

Horror Atmosphere: The Daemonic Warped Space

Next, I am going to discuss atmosphere in horror, because it is arguably the most important storytelling aspect to the genre. Horror (good horror, at least) has a specific type of atmosphere, one that creeps directly into the skin and leaves readers/viewers/players on the edge of their seat, not trusting anything that they see or hear.

The first element of horror atmosphere deals with the setting of the narrative: the Warped Space. In his essay “Lewtonian Space: Val Lewton’s Films and The New Space of Horror,” J.P. Tellote explains distorted or “warped” space as “the site of those ‘subject/object disturbances’ that distort our conventional experience of space and open onto a decidedly disturbing world” (Tellote, 5). The conventional setting—something the audience expects—has twisted into a new environment, one filled with unknown variables and situations, one that the audience does not recognize and thus fears. These spaces are “‘not empty, but full of disturbing objects and forms’, yet not so much real objects as amorphous projection of ‘all the neuroses and phobias of the modern subject’…(Vidler2000:viii)” (3), meaning the space of the medium distorts reality with the viewer’s own fears and imagination. People see one thing on the screen—an open doorway, oddly placed furniture, or a long dark hallway—but they project “phobias” that linger in their minds, creating a twisted space that blurs the objective reality on the screen and the personal fears of the audience. Lewtionian space has the “ability to place [viewers] in a space where the imagination is free to play – and to confront our very fears” (6). The space plays with the vulnerability of the human psyche. It leaves people to their own horrors, to their inner demons, and lets their fears run wild without any way of justifying their existence. This space “warps” the rational and the irrational, blurring the line between logical understanding and madness, preying on the audience’s fear of concealing darkness, eerie emptiness, and strange camera movement. The audience projects imaginative horrors into these spaces, and they then have no choice but to confront them.

This irrationality of human fear ties into the concept of the “daemonic,” the second element of horror atmosphere. The daemonic is something Eugene Thacker describes as “fully immanent, and yet never fully present…[the daemon] is at once pure force and flow, but, not being a discrete thing itself, it is also pure nothingness” (Thacker 35). In this conception, daemons are not physical creatures with horns, hooves, and pointed tails; instead, they occupy no space, have no physical presence, and are something that humans can neither touch nor describe. They are a force parallel to our human existence, much like abstract concepts of chaos, luck, or, in this case, nothingness. As a non-human entity, daemonic force is “a limit…both that which we stand in relation to and that which remains forever inaccessible to us. This limit is unknown, and the unknown, as the genre of horror reminds us, is often a source of fear or dread” (27). Daemonic force is so against the natural laws of the world that it doesn’t exist in the same realm as we do, and yet human existence is defined and haunted by its presence. It is everything we are not. This situation of a non-human and intangible force that violates all the known laws of nature frightens us, for it is human nature to fear anything that is not like us, especially if its features remain a complete enigma. Humans cannot grasp the concept of the daemonic and they never will, but it is a force that constantly surrounds them. In order to understand human existence in the horror genre, we must acknowledge the presence of the daemonic.

In horror literature, film, and gaming, the two concepts of Warped Lewtonian space and the daemonic force fuse together that twists the environment into a twisted version of imagined, psychological fear. Everything combines into one realm, one entity that I call the “Daemonic Warped Space”: A place not empty, but filled with forces that are both incomprehensible and inaccessible to humans, forces that distort our perception of reality and fantasy. This new setting is everywhere; both physical and mental, it will follow the characters as an encompassing entity with a mind of its own. Characters can never touch or restrain it because of its ubiquity. The Daemonic Warped is both the hideous monster waiting to attack, and the creaking walls that trap the character within. It is both the darkness that hides everything in shadow, and the hallucinations stemming from a character’s tormented psyche. It is the embodiment of a character’s limit, subconsciousness, and fears, and it is nearly inescapable. The Daemonic Warped space is crucial to the horror genre because it forms the fundamental basis of good narrative atmosphere: it becomes an entity itself in the fictional world, trapping the characters in a living nightmare in its distorted yet contained presence.

Mythology and Atmosphere: The Storytelling of Horror Gaming

We have discussed three mythological elements that appear in horror storytelling, along with the atmospheric element of the Daemonic Warped Space. These all relate to each other and work together to create the foundation of storytelling in horror fiction, specifically in video games.

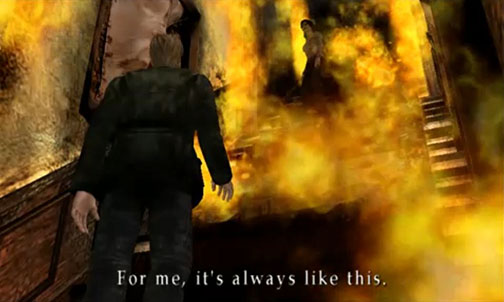

The Journey to the Underworld trope remarks on the setting of a hero’s journey, forcing the character to travel down into the world of the soul and the unconscious. The Underworld, then, is a Warped Space: a place of the dead and the supernatural, where a living being creates a conflict of existence between life and death, the physical and the mental, consciousness and dreams. In horror gaming, this descent into the Warped Underworld is the basis for the entire game. The goal for the player is to find a way out and survive the ordeal.

The Journey to the Underworld and the Warped Space come together in the murky, crawling city of Rapture in the video game BioShock. Rapture is a new place, both to the avatar, Jack, and to the player; it is a place with different rules and norms. It is a city at the bottom of the ocean, built in the 1946 and initially capitalizing on the American ideals of prosperity and success in its early days. However, when Jack descends into the city, its corridors are devoid of life and instead filled with corpses. Messages in blood are splattered across the walls, used weapons lie everywhere, and the glass walls separating Jack from the ocean groan against the silence of the city. Not only does the city subvert the norm by existing at the bottom of the ocean, but it is then distorted even further by its emptiness (a city is supposed to be busy, filled with people), its violent backstory, and its murderous inhabitants that have strayed away from both sanity and humanity. Unlike Odysseus, who travelled to the Underworld willingly, the player and Jack are thrown down into this world with neither an explanation nor any way of escaping. They confront the dark and eerie halls of Rapture with no clue as to what they are fighting or why, and yet they know they must fight simply in order to survive.

Rapture also distorts the very concepts of life and death. The life of the ocean surrounds the bloody massacre in the city, creating a conflict of existence between the living and the dead. This is also seen with the existence of Jack himself: (mostly) everyone else in the game is dead, and yet somehow you (Jack/the player) are still alive. You have to survive in a place that has been consumed by greed, corruption, and destruction. Welcome to the Underworld: a land of the dead that doesn’t greet the living lightly, where escape is a daunting and seemingly impossible task. Rapture is a city warped by death and fear, causing the player to doubt every corner, every character, and every action they take.

Both Jack and the player have no idea as to what is happening or why they are in Rapture in the first place. All they know is they somehow have to get out of the horrid, decrepit place before someone out for blood kills them. The player must survive and press forward in order to discover the secrets of Rapture, of Adam, and of Jack, someone about whom the player has very little information. Rapture, then, represents a realm of complete mystery, one that you must unearth as you proceed through the game. It is the embodiment of the Jack’s troubled psyche, dark from his amnesiac state and corrupted by his haunting previous life. His subconscious leaks into the atmosphere of the place, reminding him and the player of his tortured and distorted childhood, of his criminal tendencies, and of his “hacked” mind.[2]

During one moment in the game, the player finds the powerful shotgun lying in the middle of the floor. Once Jack equips the new weapon, however, all the lights shut off. The player can hear footsteps and sounds emanating all around, and tenses—an ambush is coming. A spotlight then switches on, lighting a small circle of the room while the outside remains covered in pitch black; from this cover, enemies pop out and attack. This switching off of the lights and revealing only a small portion of the scene portrays Rapture’s trickiness as a whole, and how the city messes with Jack’s mind throughout the game. Jack will remain “in the dark” about certain people or history of the city (and of his past), only gaining concrete knowledge through audio recordings that deliver snippets of information. The player can choose to ignore these audio logs and proceed through the game blindly, or he/she can slowly piece together the misses pieces of the puzzle, “illuminating” the story bit-by-bit. Rapture, however, will only show the parts of the story that it wants to show, not giving Jack what he wants—his past in Rapture—until the end. Before that, the avatar must deal with the “patches of light” that make his path clear, that clear up his mind about the truth of the city, and that help him discover who he is as a person. The rest of the city, though, will remain in the dark throughout much of the game, where hauntings of the city and of Jack’s past sneak out and try to destroy him. Rapture portrays Jack’s distorted psyche, and he must descend into its darkest corners in order to escape its traps and leave the demented place behind.[3]

If the Journey to the Underworld and the Warped space complement each other in storytelling, then the Unspeakable “It” Trope and the Daemonic do as well. Both the Unspeakable “It” and the Daemonic permeate the entire setting, existing everywhere and with no chance of escape. Both come together as one force in the horror games, as a monster that is both in the walls and has a physical form, hiding just around the corner waiting to scare you.

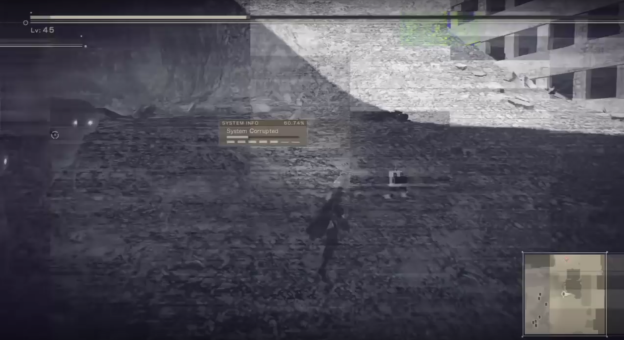

The Unspeakable “It” and its Daemonic presence appear in several games where the enemy is seemingly everywhere yet nowhere: In Metroid Fusion, the X parasite inhabits every biological organism and hunts you. In System Shock 2, the Many infect the dead to attack the protagonist while SHODAN hacks into cyberspace throughout the game. In Bloodborne, everything is a Lovecraftian horror waiting to pull you into its sick realm. Yet one game in particular stands out for portraying the Daemonic, Unspeakable “It.” SOMA, by Frictional Games, follows Simon throughout the claustrophobic halls of PATHOS-II, a(nother) facility built underwater after an apocalypse occurred on the surface of earth. The moment he wakes up in this place, he is confronted with a slimey, tarish growth on the walls, one that pulsates and quivers to the touch. The substance is the far-reaching extension of the WAU, an organic AI computer that consumes the entire PATHOS-II research facility. The computer grows and expands on walls and through computers mainframes into horrid creatures (who were former humans), within both deceased and living staff members. It infects nearly everything, and all your actions/decisions are based on its looming presence that either helps or hinders your progress. Even when you (might) decide to “kill” it in the end, its murky goop is still present in the corridors, in the systems, and in Simon. The WAU will continue to live on, and humanity will be corrupted by its organic technology.

The ever-consuming presence of the WAU is due to its programming: the computer’s main goal is to “save” the remainder of humanity by integrating humans with itself. It amalgamates with any organic form, whether living or dead, to produce a being that can survive after the apocalypse. But, are these beings really human? At one point, Simon comes across a woman who is still questionably alive, for tubes and wire run through her body, and her breathing is synced with the WAU’s organic goo that she sits upon. Other encounters with humans show their organs completely replaced with gears, lights, and machines. Catherine, the AI copy of a previous human mind that you find, is infected with the WAU on the device that houses her. Even Simon replenishes his health through the WAU at specific sites, because he too is a copy of a former human mind. Barely anyone in the game is fully human anymore, and the player can feel this shift into non-humanness as the story develops. Simon cannot escape the ever-present WAU, both physically—as it covers the walls and blocks his path—and mentally—as it constantly makes him question what he is. Is Simon a copy of a human, or another extension of the WAU’s organic components? Is the WAU really “saving” humanity, even though it is taking away basic human parts? The computer and its effect on the PATHOS-II make Simon, Catherine, and player question what it means to be alive, serving as a questionable boundary of human existence. The WAU’s consuming appearance is the daemonic force that Simon and the player must survive against, one they cannot truly escape but which instead allows them to examine their complicated existence as human and machine.

Lastly, the atmospheric element of the Daemonic Warped Space corresponds to the mythological story of the Minotaur and the Labyrinth. With the Minotaur representing the Daemonic and the Labyrinth the Warped Space, both come together to illustrate the perfect balance of physicality and psychological tension that a good horror game needs in order to make the player fear for their virtual safety.

These two elements of horror will appear in every (good) horror game, but Amnesia: The Dark Descent masters the performance. The player must walk in the shoes of Daniel, an amnesiac who must wander through dungeon hallways in Brennenburg Castle in order to uncover the truth of his past. The corridors of the castle are all giant puzzles, which the player must “solve” in order to proceed forward, serving as the labyrinth that will eventually lead him to the “Minotaur” he has to defeat. Eventually, the player comes across the iconic monsters of the game: The Gatherers, deformed humanoid beings with disgusting, gaping mouths. Unlike the avatar in BioShock, however, Daniel cannot fight against the Gatherers. His only tactic for survival is to hide behind boxes or run to a safe area. Given this and the total eeriness of the mansion, the monsters and the setting of Amnesia: The Dark Descent create a collective sense of dread for the player. You must avoid the monsters in layered, environmental darkness, making the monsters hard to pinpoint. The darkness blocks the visibility of entire rooms sometimes, and yet the player can sense when a monster is present. Most of the time, all you have to go by are the sounds the Gatherers make, a door creaking open across the room, or soft footsteps. And, because of the nature of a labyrinth, it is incredibly hard to know when and where a monster will appear. The player can only move forward by guesses, inferences, and imagination. To make matters worse, Daniel cannot stay in the dark for too long or else he will lose his sanity, blurring the lines of reality and causing hallucinations to appear on the screen. Daniel does have a lantern to light his way through the complicated maze of the mansion, but this help is no Theseus’ string: the lantern needs to be constantly replenished with oil (a resource that’s hard to come by), and the Gatherers can spot you more easily with the light on. Darkness is both your friend and your enemy, helping you hide and helping the monsters finding you. Amnesia: The Dark Descent perfectly captures feeling of terror in a game where the monsters know the “puzzle” of the environment better than you do. The Gatherers understand the tricks and complexities of the maze-like hallways, and surprise the players in rooms with undiscovered entrances. They use the long hallways where darkness covers the end to ambush you; they conceal themselves in fog-filled rooms; and they corner you into one-way corridors filled with boxes, planks, and other items that thwart your progress and bring you closer to death. The Gatherers and the mansion work together as the Daemonic and the Warped Space to create the sensation of all-encompassing danger, consuming darkness, and inevitable death for the player, bringing out the sheer dread in anticipation of a monstrous encounter.

The Daemonic Warped Space works effectively if the two elements, the Daemonic and the Warped Space, are together. If they are separated, however, the atmosphere quickly falls apart. Unfortunately, this situation can be seen in The Dark Descent’s sequel, Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs. At one point, the enemy pigs, the equivalent of Gatherers, leave the manor where the avatar wanders and begin to attack the neighboring town. The initial setting of the Machine is now left behind as the avatar walks through a more open space of the outside village, hearing the massacre of the villagers by the various pigs off-screen. The once-horrible monsters have abandoned the space, no longer using the environment to their advantage; the setting is no longer blocking the player’s path and producing suspense situations around the mechanics of the game. The Daemonic and the Warped Space are no longer using each other to create the basic element of fear: the player does not feel threatened, and the horror of the situation is lost. In order to create the tense and chilling atmosphere of the horror genre, a game must keep the Daemonic and the Warped Space together. Only when the two play off each other’s strengths to create one dreadful enemy can a player be immersed in their own fear.

Conclusion

In closing, I will look back upon one of my favorite horror games, one that represents the ultimate form of the Daemonic Warped Space and demonstrates how effective it can be in a video game. P.T. is the perfect example of the daemonic forces and warped setting fusing together to produce pure terror in the minds of players. What the game so extraordinary is it was only a demo for a much longer game (that got cancelled!), and the player does not actually do anything in the demo except for keep walking. The Warped Space distorts onto itself and repeats, causing the player to walk down a seemingly endless loop of the same corridor. You are stuck in a weird limbo where the rules of reality collapse and the dark subconscious reigns. The hallway projects different phobias and scares in each iteration of the loop, growing darker each turn, having a once-closed bathroom door now open, or inputting a different sound in the air. The monster is nothing specific; rather, it is an unknown force that you cannot fight against. It keeps changing, and the threat against you is vague in nature, making it even more terrible. Yet the “force” of the daemonic feels everywhere, like it’s the very hallway itself because it keeps messing with you. You experience the Daemonic according to its own will: it produces fears and monsters regardless of your decisions, acting alive in its own hauntedness. The only way to overcome this loop nightmare is to keep journeying, surviving the loop and experiencing the sadistic presence. The continuous, warped hallway remains alive with the Daemonic and keeps morphing to throw you into further torment, producing scarier circumstances at each turn. Your psyche does all the work, trying to piece together the story, the monster, the setting, and the way to escape, yet halting when confronted with an unknown entity due to your imagined fear.

The best example of this occurs on the fifth iteration of the loop. You turn the corner to face the exit door, and instead spot the first being in the game standing your way: a deranged, mumbling, crooked woman sways in your path. You know approaching her is a bad idea, but that is the only way to continue. So you walk forward, and, right before you reach her, the lights shut off, leaving you in pure darkness. It is the most terrifying thing because the setting and the monster are both fooling with you, and you as the player know that there is nothing you can do about whatever will happen next. You simply must continue forward in a darkness where a monster may or may not be, and that is utterly horrifying. The Daemonic Warped Space is an essential atmospheric element to horror storytelling and gameplay mechanics, for it makes you confront the fear of the unknown, and, no matter how hard you try, you will be going against monsters beyond your control and knowledge—monsters that work with the dreadful environment to make your life absolutely miserable.

Laila Carter is a featured author at With a Terrible Fate. Check out her bio to learn more.

[1] From “The Dunwich Horror”—Someone describing the invisible monster terrorizing the village: “‘Bigger’n a barn . . . all made o’ squirmin’ ropes . . . hull thing sort o’ shaped like a hen’s egg bigger’n anything, with dozens o’ legs like hogsheads that haff shut up when they step . . . nothin’ solid abaout it—all like jelly, an’ made o’ sep’rit wrigglin’ ropes pushed clost together . . . great bulgin’ eyes all over it . . . ten or twenty maouths or trunks a-stickin’ aout all along the sides, big as stovepipes, an’ all a-tossin’ an’ openin’ an’ shuttin’ . . . all grey, with kinder blue or purple rings . . . an’ Gawd in heaven—that haff face on top! . . .’” http://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/fiction/dh.aspx (Seriously, read this story).

[2] I am not trying to spoil the game entirely, but instead just hope to give readers a hint of the story. If you want to know more, you’ll have to play the game for yourself.

[3] Or not, depending which the ending the player gets.