–by Laila Carter, Featured Author.

Equipped with her four guns and always waging war against the heavenly army, the Umbra Witch Bayonetta has become one of the most recognizable female characters in gaming. Some people have (understandable) qualms with Bayonetta as a character: they claim that her over-sexualization – making someone excessively sexual whether in looks or actions – only attracts people to look at her body for pleasure, and that viewers do not respect her as a women of agency. However, judging by the many reactions people had when she was announced as the newest character in the last Super Smash Brothers game, I do not think that this is true. People respect Bayonetta and her abilities despite her over-the-top sexuality, or, as I argue, because of it. She is one of the few women in video games who is overtly sexy yet owns her sexiness, incorporating it in her personality. She is not simply some side-girl with no purpose other than to show off her huge breasts. She is the main star of her game and kicks major butt with witch power and sexual grace, showing off a butt-shot here and there simply because she feels like it. Bayonetta has agency of her own over-sexuality; She has the ability for a character to create and change the way she presents herself, and she does so by owning her image and enjoying every minute of it.

Let me be clear about the goal of this article: I am not discussing whether or not Bayonetta is a feminist icon in gaming. That discussion is an ongoing one[1] that will probably never be fully answered, but it has no place here. I am instead discussing how Bayonetta uses her sexuality in a different way than most women in video games.

Bayonetta, The Male Gaze, and Agency

When watching film or animation, certain topics tend to appear when analyzing how and why a scene is shot. The most relevant film term here is the term “gaze”; its definition is to “look at steadily and intently, in fixed attention.” In film studies,[2] “the male gaze” specifically refers to when the camera positions itself so as to objectify the woman (or women) on screen. The audience does not view the woman as a person, but rather as an object, thanks to camera angles and movement, character attire, or scene setting (for a simple example, a woman lying in bed in a provocative manner). You can use these terms when talking about any visual medium, like comics, art, television, and video games. The types of art that use the “male gaze” depend on spectators’ scopophilia: deriving pleasure in looking at a woman for sexual interest. Scopophilia is what feminist film critics argue heavily against because the “male gaze” reduces women on screen to an object rather than to a character. By “object,” I mean a thing that one can own and handle as their own, and by “character” I mean an fictional entity representing an intelligent and sentient being that has its own independent existence. Critics and gamers have argued against Bayonetta’s entire character because of the “male gaze” the game’s cinematics produce; they claim that she invites spectators to look at her for her over-sexual body and not for her actual character.[3]

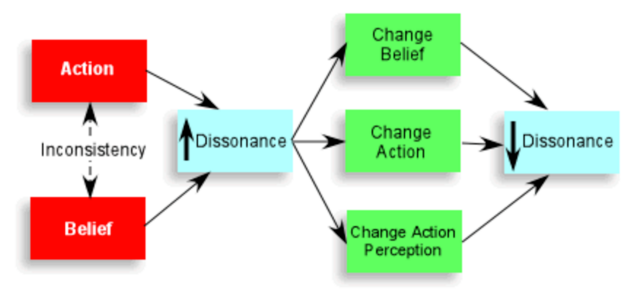

While I agree that the “male gaze” is a problem in film and animation, I do not think it can fully apply to Bayonetta’s character. To demonstrate, I will compare Bayonetta to the comic heroine Power Girl of the DC Universe, and to another controversial video game heroine, Tracer from Overwatch. Through Power Girl and Tracer, I will show the inconsistency between their character design – the way they look – and their character development – the way they act, feel, and understand the world as a whole. The inconsistency between design and development is a common way to distort female characters and attract the “male gaze,” having viewers focus on appearance rather than the overall character; And yet, this flaw of design and development does not exist within Bayonetta’s character.

The comic book heroine Power Girl is a tough, short-tempered superhero who has all the superpowers of Superman, except that she as a very low tolerance of nonsense. Her outfit, though, is more suggestive. It is a leotard, but it has a huge hole at the chest, which reveals Power Girl’s unnaturally huge breasts. While Bayonetta does possess unnatural body portions, mainly in her freakishly long legs, her sexual organs – breasts and backside – are fairly normal. Power Girl’s obviously enlarged and showcased breasts attract the “male gaze,” inviting viewers to read her comic for sexual pleasure rather than for her actual story. Her sexualized character design contradicts her character development, ignoring her no-nonsense personality, making it apparent that her outfit and body were not of her own design. The only explanation for these features is that the creators wanted her to look that sexualized; nothing in her own personality and behavior suggests that she would ever wear such an outfit (especially with breasts as big as those – one jump and they are flying right out).

Another good example of character inconsistency comes from a recent controversial pose of a female character. In Blizzard’s new team-based shooter Overwatch, the most iconic character, Tracer, had a new victory pose that some people did not like.[4] In the shot, she had an “over-the-shoulder” look, meaning her back was as the camera while her head looks over the shoulder. With her back to the camera, she shows off her orange behind,  fully outlined in tight spandex. Tracer is a fun-loving, silly, and friendly character, but the pose had nothing “to do with the character [Blizzard] is creating.” The argument does not call out all female heroes in the game (such as a sniper who purposely “flaunts her sexuality” to distract her enemies, so it makes more sense for her to be showing off her behind), but does not approve of Tracer’s pose because it showed that “at any moment [the creators] are willing to reduce [female characters] to sex symbols.” The pose contradicted her personality and was very jarring in comparison to her character development. The article sparked a huge discussion to the point where Blizzard studios removed the pose altogether.[5]

fully outlined in tight spandex. Tracer is a fun-loving, silly, and friendly character, but the pose had nothing “to do with the character [Blizzard] is creating.” The argument does not call out all female heroes in the game (such as a sniper who purposely “flaunts her sexuality” to distract her enemies, so it makes more sense for her to be showing off her behind), but does not approve of Tracer’s pose because it showed that “at any moment [the creators] are willing to reduce [female characters] to sex symbols.” The pose contradicted her personality and was very jarring in comparison to her character development. The article sparked a huge discussion to the point where Blizzard studios removed the pose altogether.[5]

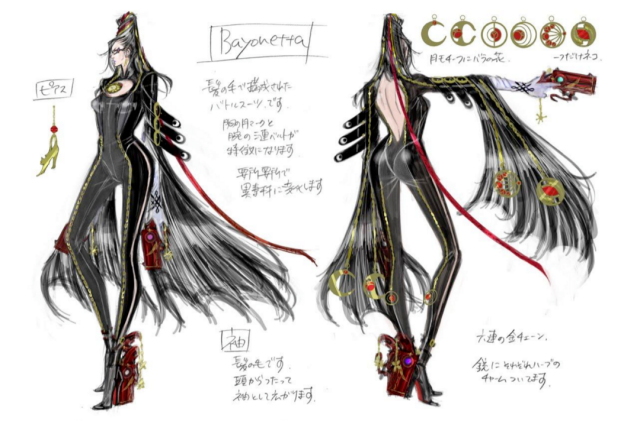

On the other hand, Bayonetta’s black, detailed body-suit establishes her as a sexy character. She is a flirtatious and dramatic dominatrix, not afraid of showing off her sexy body to anyone who is willing to watch. Her skin-tight outfit, in both games, pronounces her behind, but not so much her breasts. It creates a strange balance of sexualization, not making her too top-heavy but still allowing her to flaunt her body. It would not make sense if she wore a modest outfit, just like it does not make sense that tough and cranky Power Girl wears an overtly suggestive one. Her design works well and builds upon her character development, making her a more consistent character overall, one that does not feel like the creators wanted to give her a sexy overfit for the sake of sexiness.

The most important aspect about Bayonetta’s character design is that her sexuality does not seem out of place. Bayonetta takes full control of her sexiness and unashamedly shows it off. She is a dominatrix, sexy yet intimidating and powerful. She poses erotically as she performs killing blows on her enemies. She summons demons fully naked, making the most ridiculous and sexy stances in the game. Everything about Bayonetta reflects over-the-top female sexuality that startles, shocks, and impresses its viewers. Her hair-woven outfit and appearance in general match her abundant sexiness in her speech and actions. Unlike many other female character designs that have no business being sexual, Bayonetta’s design encompasses her sexuality in all aspects of her person: her outfit, her personality, her behavior, and her gameplay (more on that later). She has agency – the ability to create and change – over her sexuality and revels in it, using it as a means to portray who she is as a person. If you take away her sexiness, Bayonetta would cease to be Bayonetta.

In both of Bayonetta’s games, she exhibits her over-sexualization in two media: cutscenes and gameplay. Both produce different iterations of Bayonetta, as the prolonged cutscenes are more blatantly sexual than the gameplay, but the latter produces many instances of Bayonetta flaunting her body, triggered by the player’s choice in attack. I will discuss both separately in order to further argue my case that Bayonetta has the ability to create and change her own over-sexuality.

Bayonetta in Cutscenes

When you are first introduced to Bayonetta, chances are that you think she is just another over-sexualized female character in gaming. You load Bayonetta 2 and start the story by watching the first cinematic cutscene of the game. You see Bayonetta in a fancy shopping outfit strolling down the sidewalk, when a fighter jet barrels towards her. She stops it, leaps on top of another one in midair, and faces the horde of angelic monsters that confront her. They attack, she dodges; but in the process, the angels’ weapons tear away her outfit, presenting her in the middle of the sky fully naked (luckily, shading prevents the game from being pornography). She then summons her hair to wrap around her nude body, creating her outfit (yes, it is made out of her hair) as she poses dramatically. She then proceeds to destroy the angels in a series of sexy and over-the-top attacks before the game drops you into gameplay.

Bayonetta’s cutscenes are, to put it mildly, absurd.

If players manage to survive the opening cutscene, then they realize Bayonetta’s over-sexualization definitely earns the word “over.” Bayonetta performs ridiculous stunts, flying through hell on a giant demonic horse, avoiding weapons by spreading her legs, or participating in a sexy posing contest with an enemy angel. She may perform her actions in sexual ways, but everything happens so fast and so outrageously that it leaves one in utter surprise rather than in sexual pleasure. Bayonetta will summon a demon and slap an angel’s behind in the same scene, and the player can barely process all the images and what they imply. The over-sexualization of the opening scene is mainly for shock value: the combination of the presentation and subject material makes it hard for the viewer to take everything seriously. Bayonetta’s sexuality is less for visual pleasure than for people to stop and question what they just saw, to rethink the entire situation that Bayonetta is in. This is especially true if you play the game for the first time and have never seen the cutscenes. Bayonetta’s over-sexualization is so absurd and over-the-top that it becomes comical – it is nonsensical shock-value entertainment. Even when players watch the cutscenes and Bayonetta’s poses for the third or fourth time, nothing gets old; it’s still fascinating how Bayonetta creates an extravagant show out of her own sexuality.

Bayonetta in Game Design

People are sometimes rightfully frustrated with female characters in video games because of their narrative placement: that is, when a woman appears in the narrative and what she does to impact the story. Many women appear in DLC, or in no gameplay at all–they are there to help, but are never fully playable. They are in the game to be rescued, to help the main protagonist but never accomplish anything by themselves, or for the infamous factor of sex appeal. This kind of representation of women becomes more frustrating when the designers decide to sexualize female characters that are crucial to the narrative. For example, Kaine from Nier is not playable at all and shows up to assist the protagonist Nier most of the time. She[6] is important to the story, but her apparent lack of agency over her own story (she gets possessed by a monster at one point, and it’s up to the player whether she lives or dies) can be very disheartening for people who want her to have more control in her own narrative. In addition, her skimpy outfit barely covers her body, revealing most of her behind,[7] and greatly contradicts her cold and anger personality (much like Power Girl). Her character placement is frustrating because her lack agency over her own story and her contradictory design, which invites the “male gaze” to mostly “gaze” at her cutscenes. Kaine’s sexualized (and unnecessary) character design and placement makes it seem like she is in the story mainly for the player’s pleasure, and not for a consistent character development.

Bayonetta, on the other hand, is the main and most prominent character of her game (it is named after her). Her character placement is the center stage, and the player does most of the action through her character. She is playable 98% of both games,[8] and, more importantly, she is the active character of the game. Active characters change the environment and story according to their own will.[9] In the first Bayonetta, she decides to head to the ancient city Vigrid to figure out her past and find her lost memories. Without spoiling anything, in the end she reclaims who she is as a person and fights for both what’s right and for the safety of the world. In Bayonetta 2, she decides to venture into Inferno itself, ignoring the improbability of survival in order to save her near-dead best friend Jeanne. She rekindles relationships with many characters and saves the world in the process, again. In the first Bayonetta, the plot revolves around her self-discovery and asserting her right to live, and in the second Bayonetta, the plot follows her selfless adventure to save her one true friend. She is not a side character present in order to assist the protagonist, nor is she unessential to the plot. The narrative would not exist without her taking charge, without her deciding her own fate, and without her overcoming all obstacles with the strength and willpower of her one-woman army.

Not only does she direct the game’s story (as a well-designed character should do) by making her own decisions and changing the course of the narrative, but Bayonetta has also become one of the most powerful figures in video games. This is important because, as I have stated before, many women who are sexualized are portrayed as weak compared to other characters (protagonists especially) in the story. On the other hand, Bayonetta is ridiculously strong and is arguably the strongest character in the game. In terms of gameplay, Bayonetta has one of the most fluid and powerful combo systems containing a large variety of options that never make the gameplay dull. She acquires different weapons that can pair with other weapons to form even more combos. These weapons range from sharp and deadly swords to a giant hammer, from ice skates to whips, and from a living scythe to a bulky grenade launcher. Every weapon has a unique demon that Bayonetta can summon either if the player uses the right attack combination or if the player initiates umbra Climax, a mode in Bayonetta 2 in which Bayonetta’s attacks increase in magical strength. In this mode, Bayonetta manifests larger versions of her normal attacks and can summon her large personal demons more easily. Everything on screen explodes in purple magic with Bayonetta glowing, and the players gets a rushing sense of exhilaration. They can feel her magical power whenever they destroy a fleet of angels with her giant, demonic punches, and they can feel the true strength of an Umbra witch when they annihilate a boss as big as battleship. The player feels powerful through Bayonetta, that they, through her, can conquer any obstacle standing in the way. Cutscenes may show off some of Bayonetta’s fighting power in sexy and comical ways, but players get real understanding of her ridiculous and amazing strength through gameplay. Her combos and demonic summons demonstrate the full force of an Umbra Witch, a being who is not to be trifled with.

To top it off, Bayonetta incorporates her sexiness in all of her gameplay. Some attack combos have Bayonetta perform acrobatic stunts, which she finishes with dramatic and flirtatious poses. For example, when Bayonetta attacks with her “breakdance” move, she spins around on the ground, shooting bullets in a whirlwind that does great damage to nearby enemies. She stops this attack by lying on the ground with her behind in the air, arching her back and winking directly at the camera (breaking the 4th wall). Torture attacks are special summons that produce great damage or instantly kill enemies. When she summons them, Bayonetta usually performs another sexy pose; for example she can summon a tombstone to flatten enemies, and when the heavy stone lands, she squats with her knees spread and makes a face, all like she is posing for the camera (the flattened enemy is behind her). The funniest are the punish attacks, where she will sit on top of a fallen enemy and slap them to death, usually on their butt. It is highly sexual and creates the picture of Bayonetta as a dominatrix; yet the player prompts Bayonetta to use her punish attacks because they are incredibly efficient in dealing with enemies, not just because they are sexy.

The most sexually revealing of Bayonetta’s attacks are her demonic summons, yet they are the most spectacular parts of the game. Bayonetta summons her large inferno demons at the end of mini boss fights, boss fights, after certain attack combos, or during umbra Climax in Bayonetta 2. She can call forth beasts such as Gomorrah, a dragon, Diomedes, a Unicorn whose horn is a giant sword, and the infamous Madame Butterfly, her personal female demon whose limbs Bayonetta summons the most for fighting. The witch even uses her to fight against an equally strong opponent angel, resulting in an grand aerial battle between Bayonetta and a Lumen Sage in the foreground (the fight the player controls) and between the giants of Madame Butterfly and the angel Temperantia in the background. Demonic beasts encompass the entire screen, finishing off other large enemies with ease. In order to summon such monsters, Bayonetta uses her hair; her hair, though, is what makes up her clothing, so in order to summon demons, Bayonetta has to be naked. It is a little startling when a player first summons Madame Butterfly’s fist and Bayonetta appears nearly naked on the screen. It is not complete nudity: gray shading covers her breasts, stomach, vagina, and behind, but she still does not wear any clothes. She will appear like this in regular combat, whereas in cutscenes she will be naked, but with her hair blocking anything inappropriate. When she summons demons for a grand finisher, her nakedness is more suggestive as the gray shading is no longer present and only weaves of hair cover her private areas. It is over-sexual to the extreme: the over-the-top, ridiculous, and absurd nature of Bayonetta’s near-nudity adds even more to the shock value of game, making players ask whether if what they saw on screen really happened. Playing as Bayonetta gives the player a whirlwind of initial confusion and shock, but it never deters from the thrill of overpowering enemies by summoning a giant canine to tear them to shreds.

Bayonetta’s attacks are graceful and powerful, exhibiting the female body throughout the gameplay. Her moves mean business, and that’s what is so great about Bayonetta. She is over-sexualized, but she defeats her enemies with overwhelming strength. She fights legions of both Paradiso and Inferno, angels and demons, minions and giant bosses, and still is able to pull a dramatic pose at the end of fighting. Her prominent display of her feminine body is empowering; in art media, the female body is usually presented as sign of weakness – something undesirable for the self to become – or as sexual interest – something desirable for the self to possess. Bayonetta demonstrates through her gameplay that having a female body does not make a person any less powerful: that one can have sexy breasts or a sexy behind and still defeat any enemy that comes one’s way. She proves that the female body is not a sign of weakness but of strength, because she accepts the body she was given and is proud of it.

Conclusion

Bayonetta’s agency of her over-sexualization makes her a wonderful female character. Many female characters have no agency at all, making their visual design mismatch their personality and behavior, thereby creating bad character design. With many fictional female characters – whether in movies, TV shows, animation, comics, or video games – female sexuality is present for the spectators, and not for the woman herself. She is sexy for the appeal of the audience, but not for her own tastes and pleasure. Bayonetta, however, fully enjoys her over-sexualization and professes it to the world, which is apparent in both cutscenes and gameplay. Who would perform sexy poses while in the midst of battle if they did not love their own body? She has full agency over her entire character – she owns her outfit, her sexiness, her personality, her narrative actions (meaning decisions she makes within the story),[10] and her goals, and nothing stops her from believing in herself, sexiness and all. Her sexiness does not make up her entire character, either: she is courageous, witty, commanding, headstrong, and compassionate for her friends and family. Bayonetta is not a character who only has a game to exhibit her undying sexiness: she is there to teach her enemies a lesson and display real emotions at the same time. Looking sexy while doing it is just a good bonus. Bayonetta exemplifies that it is okay for a woman to be sexy if the woman wants to be sexy; you can have characters with sexy breasts, a sexy butt, and a sexy personality, and that’s fine as long as the characters are okay with it. This applies to both fictional characters and real people, male and female. Yes, it would be outstanding to have a female character who is just as powerful, prominent, and successful as Bayonetta without the intense over-sexualization; but I, a straight woman, do enjoy Bayonetta’s abundant sexiness because, for once, she also enjoys her own sexiness and celebrates it for her own sake.

Laila Carter is a featured author at With a Terrible Fate. Check out her bio to learn more.

[1] http://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2014/10/femme-doms-of-videogames-bayonetta-doesnt-care-if.html

[2] Feminist Film Studies, to be precise.

[3] https://gomakemeasandwich.wordpress.com/2011/06/03/bayonetta-and-the-male-gaze/

[4] The original post and the huge discussion it caused: http://us.battle.net/forums/en/overwatch/topic/20743015583. Another video explaining the pose: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hf5SdrJoOdc

[5] The only reason I had any problem with the pose is because Tracer had no butt to show off – it’s non-existent and looks weird to me.

[6] Kaine is a hermaphrodite, but most people use she/her pronouns to describe her.

[7] I understand the argument for why she reveals most her skin – that she must expose the most skin to sunlight in order to control the monster possessing her – but it’s still shady. It is also in great contrast to her cold, calm, and shy personality.

[8] The other 2% you play as Jeanne, her best friend, and Loki, an important side character.

[9] For more on active and passive characters: http://readingwithavengeance.com/post/77195680492/on-writing-active-vs-passive-characters

[10] As a video game avatar, Bayonetta cannot completely control her actions: her fighting and traveling is in the hands of the player. But in terms of her crucial decisions and how she responds to certain events, Bayonetta has control.