Since the beginning of With a Terrible Fate, I’ve made passing comments about how deeply the storytelling of the Final Fantasy XIII trilogy offended my sensibilities, both as a player and analyst of video games. On the first day of my three months analyzing Majora’s Mask, I discussed the Zelda game’s value by showing how it succeeded where Lightning Returns failed; when I discussed my fears about Square Enix dividing the Final Fantasy VII remake into multiple games, I cited the weak episodic storytelling of the XIII saga as prima facie reasons to worry about Square’s ability to tell one story across multiple games. Yet despite constantly using the XIII trilogy as fodder for broader critiques, I have never yet devoted an article to tackling the problems of the series head-on.

Well, with today at last marking the release of Final Fantasy XV, I found it a fitting occasion to turn my full attention to Final Fantasy XIII, as something of a personal reflection on why I was so let down by the trilogy. I do view the trilogy as a fantastic failure in storytelling, but the undertone of this critique is the quiet hope that Square learned its lesson and remembered how to tell stories. This, I think, is the core issue to keep in mind as FFXV finally enters the universe of game criticism in the coming weeks: remember that FFXIII also “looked pretty” and had a decent enough battle system; its colossal failure was one of storytelling, and I believe that storytelling is the measure by which FFXV will stand as a masterpiece or fall as an epic waste of time and resources.

Sadly, I could probably spend as long picking apart the FFXIII trilogy’s problems as I spent analyzing Majora’s Mask (but don’t challenge me on that–it wouldn’t be fun for anyone). So today, I’m just going to focus on Final Fantasy XIII-2. I’ve long thought that, of the three games in the trilogy, FFXIII-2 was the one with the most redeeming features and the greatest narrative potential. The problem is that FFXIII-2 is, in a surprising and sad sense, a very poignant story trapped inside of a very poorly composed story. The project of this article is to explain what I mean by that claim; in particular, I want to show you how the very structure of Final Fantasy XIII-2’s universe renders its narrative shortcomings tragically ironic, perhaps even in a way that can give disappointed players a new appreciation for a game that fails in an almost beautiful way. I’ll first argue that, sacrilegious though it may sound to say so, FFXIII-2 was poised to be the spiritual successor of the classic Chrono Trigger. After that, I’ll show how the overall framing of FFXIII-2‘s story destroyed what initial potential the game had–in fact, I’ll argue that it suffers from failures similar to those of Assassin’s Creed III, but suffers from those failures to an even greater extent than ACIII does. Lastly, I’ll combine these two strands of analysis to show how the game becomes a tragically ironic narrative failure. In the end, we’ll walk away with some lessons in how stories can fail–and, hopefully, how stories can succeed.

I’m still waiting for a justification of why this Moogle was so crucial to the plot of XIII-2.

Not a Hallway Anymore: Temporal Overworlds

One of the most common criticisms of the first entry in the FFXIII trilogy–named simply Final Fantasy XIII–was that its world and story were overly linear, meaning that the game consisted in a singular path from the beginning to the end of its narrative with very little by way of exploration or divergence from that path. One of JonTron’s most popular video’s, criticizing precisely this aspect of the game, bore the fitting title “Final Hallway XIII” in reference to the game’s severe linearity. So, you might expect that the developers, in crafting a sequel to FFXIII, might compensate for this aspect of the original game by making the sequel substantially less linear, with a variety of different paths and narrative outcomes to explore.

And indeed, less linearity is exactly what we see in FFXIII-2; in fact, the structure of the game’s world and narrative is radically non-linear. What I mean by ‘radically non-linear’ is that, where the worlds of most games tend to be spatially organized, the world of FFXIII-2, at its highest level, is actually structured in terms of time. The player’s main interface with the game is the Historia Crux, a metaphysical space that allows them to access various moments across time–some of which occur in alternate timelines. The Historia Crux is analogous to the ‘world map’, or ‘overworld’, of many other games: the global space that contains all of the various locations to which the player can travel over the course of a game’s narrative. Yet instead of being a broad swath of space, the Historia Crux is a broad swath of time: we could justly call it a temporal overworld in the sense that it fundamentally structures the game’s narrative and locations based on time rather than on space.

The Historia Crux matrix of gates to locations throughout time and timelines.

One might even say that the story of FFXIII is about linearity and non-linearity in narrative. The Historia Crux is made possible by a variety of paradoxes that corrupt time with impossible events following the end of FFXIII‘s narrative, when the goddess Etro intervened to save the player’s party of characters, thereby distorting the flow of history. One way of viewing the goal of FFXIII-2, then, is to travel through time resolving these paradoxes, trying to restore order to the timeline. One might actually see this as a clever response on the part of Square to the linearity criticisms about FFXIII: by resolving paradoxes in FFXIII-2, the player is able to travel to a variety of potential timelines and witness several paradoxical outcomes to the game’s history–yet all of this is done in service of restoring order and linearity to the storyline, ultimately reaching the game’s singular, canonical ending. It’s easy to interpret this as a metaphor for the tension in games between the need for games to present multiple possibilities on the one hand, and the need for games to tell a coherent story on the other hand: for players’ choices to matter in game narrative, multiple outcomes to events must be possible, and yet this increasing variability in the game seems to cut against the grain of a well-articulated story with fixed, carefully arranged events.

So far, so interesting. While I haven’t yet said much at all about the particular content of FFXIII-2‘s story, the form of its world certainly seems like an interesting basis for telling a tale that plays on the special features and constraints of video games as a medium. And it’s worth noting at this juncture that this isn’t a radically new idea: in fact, it picks up on some of the central mechanics and themes of a much older game of Square’s: Chrono Trigger.

The Epoch’s time-traveling interface in Chrono Trigger.

Though it wasn’t structured around paradoxes, Chrono Trigger did gain fame for its time-travel narrative structure, complete with a wide variety of potential game outcomes depending on choices the player made, when the game’s ultimate enemy (Lavos) was defeated, and so on. Released in 1995, the game was ahead of its time–no pun intended–in the way it built a robust game narrative out of multiple possibilities and timelines for the player to explore. This is the tradition in which FFXIII-2 followed; you can even see echoes of the time-hopping interface of Chrono Trigger’s time machine, the Epoch, in the design of the Historia Crux.

Caius with one of many ill-fated Yeuls.

But FFXIII-2 goes beyond merely elaborating the structure of Chrono Trigger: in the details of its story–or rather, one of its storylines–it makes the game’s time-based narrative deeply poignant in a surprising way. The central antagonist of the game is Caius Ballad, a man who has been made immortal by being endowed with the heart of the goddess Etro–the Heart of Chaos. He is the designated guardian of Yeul, a Seeress with a double-edged gift: the young girl can see the future, but her lifespan shortens each time she does so, causing her to die young, only to be reincarnated thereafter. Thus the immortal Caius, knowledgeable of all time thanks to Yeul’s visions, has also had to watch countless Yeul’s die in his arms, “carving their pain on his heart” every time. Caius’ mission in the game is to kill the goddess Etro, from which time and history flow, in order to end time itself: he only wants to do this in order to end Yeul’s suffering by putting a stop to the cycle of her dying by degrees every time she sees the future.

Noel and a dying Yeul.

On the other hand, we have the protagonist Noel: one of the player’s two characters, who gets wrapped up in a quest to change the future and resolve the timeline. Growing up, he knew both Caius and one incarnation of Yeul; he refused to become Yeul’s guardian when he learned that he had to kill Caius in order to do so. As he travels throughout time, he clashes with Caius and meets numerous other incarnations of Yeul; thus he comes to understand both the fate of Yeul and the pain endured by Caius as Yeul’s companion and protector. In the game’s final battle, Noel confronts Caius and challenges his views about Yeul: though Caius believes Yeul to have been cursed by Etro to die and be reborn countless times, always living a short life, Noel tells Caius that he knows Yeul wanted to come back because she loved Caius and wanted to be with him, time and again.

The closer you look at the story of Noel, Caius, and Yeul in relation to the overall architecture of FFXIII-2‘s narrative and world, the more poignant the story becomes. The very act of the player and Noel progressing through the story and constantly changing the future causes Yeul to have more visions, thereby shortening her life and killing her more quickly; Caius, the game’s final villain, wants Noel to be strong enough to kill him so that, by Caius dying, Etro will die too (since his heart is her heart) and Yeul will be free from seeing history. And as Noel continues in his journey, he comes to understand both Caius and Yeul, all the while unknowingly unwinding the coil of fate to the point where he is strong enough to kill Caius, and Caius forces him to do so. And on top of all this, perhaps most impressively, this narrative perfectly mirrors the act of playing the game: as the player explores and exhausts all the game’s narrative possibilities, she becomes more invested in and knowledgeable about the characters, all the while progressing the story to the point where the game reaches its conclusion, effectively ending the timeline of the game’s world and terminating the player’s interaction with the various timelines. This is a story shockingly rich with layered conceptions of time, sympathy, pathos, and the tension between possibility and fate.

I started out this article by claiming that FFXIII-2 was a game with tragically ironic narrative shortcomings, but thus far I seem to have been describing an incisive, acutely self-aware game with a moving narrative. So where’s the problem? Well, you might have noticed that I said above that Noel is one of the player’s two characters–and it’s the other one of these characters that makes trouble for the game.

Tragedy and Time

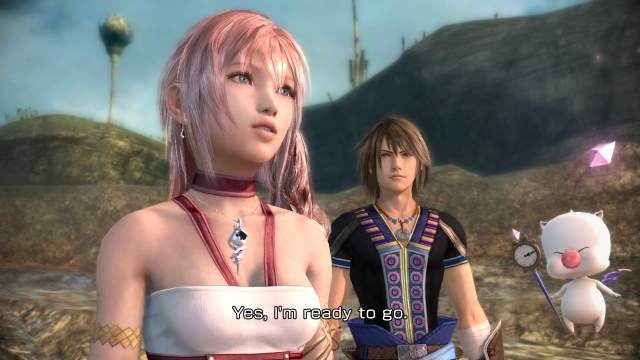

In a nutshell, the problem for Final Fantasy XIII-2 is that the story I just related to you above is relegated to the status of a sub-plot: Noel and his cohort are effectively supporting characters in service of the player’s other controllable character, Serah Farron. The game is principally conveyed through her perspective, and her goal–the primary impetus for the game’s overall narrative–is to effectively undo the world and story of Noel, Yeul, and Caius.

Note here that Noel is backgrounded relative to Serah and Mog the Moogle, and that Serah is the one deciding that the party is ready to go. In these respects, this picture symbolizes pretty much every aspect of the problems I’m pointing out for the game.

Serah is the sister of Lightning, who was a major character in FFXIII and the primary protagonist (and only player character) of Lightning Returns, the last entry in the trilogy. She is engaged to Snow, another key character from the first game that gets downgraded to little more than “Serah’s fiancée” in FFXIII-2 and Lightning Returns. The overarching narrative of FFXIII-2 is that, as the time paradoxes began (following the events of FFXIII), Lightning was effectively erased from history, trapped in Valhalla, the realm where the goddess Etro dwells beyond time. Serah is the only one who remembers Lightning’s presence after the events of XIII-2, due to the paradoxes; Lightning, from Valhalla, sends Noel to join Serah on a journey to fix time, along with Mog, a Moogle who guides Noel and Serah through the world and time.

Personally, Serah doesn’t strike me as a very interesting character–she seems to, for most of the game, have a generally bad time in the style of Sandra Bullock in Gravity, and to be generally two-dimensional besides this–but it’s not especially insightful to critique a character by saying tit isn’t one’s personal cup of tea. I think the more interesting problem with Serah is actually much deeper and harder to forgive than anything like her likability: the problem is that Serah’s epistemic perspective is directed outside of the game’s universe. The entire thrust of Serah’s storyline is that she remembers her sister when no one else does, and wants to restore time to the way she remembers it; in other words, she remembers the events of Final Fantasy XIII, and is trying to reestablish them in a world that is radically different. (Note, as an aside, that this is one of the reasons why it’s so challenging to make sense of the series’ overall consistency: the very premise of time paradoxes in FFXIII-2 effectively undoes many narratively central elements of FFXIII, and similar anti-plot devices bridge the gap between FFXIII-2 and Lightning Returns.) So the primary objective of the game’s narrative, as presented through the lens of its focal character, Serah, is to undo the world of the game by changing history to reinstate the world of the previous game. So Serah’s narrative isn’t simply a “distraction” from Noel, Caius, and Yeul’s narrative: it actually actively disqualifies it as relevant, since that narrative constitutes part of the world that Serah is aiming to undo. Indeed, even when Serah is identified as a Seeress who, like Yeul, can see the future at the cost of her life, this fact that could potentially unify the two narratives seems nevertheless to be something that Serah’s narrative tries to overpower and disqualify: she decides to continue trying to change the future despite the fact that it may cost her life. Thus when Serah does die at the end of the game as a cost of her visions, the death doesn’t beautifully tie her story and fate together with Noel’s–rather, it just puts a final emphasis on the bizarre fact that the game you just played forced you to focus on a player who never wanted to be in the world of the game.

This problem is deep and inescapable because the narrative of FFXIII-2 virtually always focuses on events through Serah’s perspective. This is important to note because there are multiple ways in which games can intermingle good and bad narratives, and these ways bring about different effects in the overall narrative. It’s useful in this regard to contrast FFXIII-2 with the case of Assassin’s Creed III.

Desmond and the Animus of Assassin’s Creed.

Again, regulars to the site will know I’ve been harshly critical of ACIII in the past, mostly in virtue of what I see as a baseless use of an alien-like First Civilization dominating and confusing a narrative about Templars fighting with Assassins; I first detailed this in an article comparing the “aliens” of Assassin’s Creed to the “aliens” of Majora’s Mask. Roughly, my gripe against the game is that the imposition of the First Civilization discounts the value of any agency the player appeared to have within the world of the game, thereby undercutting the entire point of having played the game; this is especially clear when Desmond killed with little narrative justification or explanation at the end of ACIII. But it’s crucial in understanding ACIII to note that there are two layers to the narrative: we have Desmond working as an assassin in present time, and we also have him accessing and living out the memories of his ancestors in the past via the Animus. When engaged in the Animus, the broader storyline of Desmond, the First Civilization, etc., largely fade away: instead, we are left with a compelling narrative about a Native American ancestor, Ratonhnhaké:ton, taking part in the American Revolution, becoming an assassin, and undertaking a deeply personal quest for justice.

The key thing to notice about the above ACIII example is that the layered aspect of the narrative, with the Animus interface serving as a barrier between Desmond’s story and Connor’s story, allows us to effectively consider each narrative independently of the other, while still being able to consider them compositely if we so choose. Despite my qualms about the overall game and series, I quite enjoyed Ratonhnhaké:ton’s story in Assassin’s Creed, and the overall narrative structure allowed me to enjoy it without the overarching Desmond narrative severely impeding it. But this isn’t the case in FFXIII, because there is no Animus-like interface between Serah and Noel’s narratives: Serah is the player’s primary conduit to the entirety of the game’s world–the world she wants to undo. Even in the momentous final confrontation between Noel and Caius that I described above, we find Serah collapsed a few yards from them on the beach of Valhalla, being sad and generally having a bad time. We’re trapped in the perspective of someone who doesn’t belong or want to participate in the world in which we as players as participating, and that is the crux of FFXIII‘s failure.

Conclusion: A Tale of Tragic Irony

If you like irony, then there’s a silver lining for you in all this: even though the overall architecture of FFXIII-2 spoiled what could have been a moving and cerebral story, it does leave us with some tragic, dramatic irony in the way that Serah’s narrative interacts with the narrative of Noel, Caius and Yeul. Noel, Caius, and Yeul are deeply enmeshed in a universe rife with paradoxical possibilities and timelines, trying understand the best way to shape their world and each other as they grapple with the complex perspective and sympathies that come with witness life, death, and pain across countless generations and potential timelines; yet all of their struggles to understand and make meaning ultimately depend on the whim of a player whose actions are being filtered through the lens of a girl who has no intrinsic stake in the events or native inhabitants of the world in which she finds herself. This almost recalls classic Greek tragedy in how laughably ironic it is: as characters wrestle with their humanity and universe, their fate rests in the hands of someone whose priorities are entirely elsewhere–literally in a different game.

If there’s any larger takeaway here, I think it’s this: the worlds and metaphysics of video game worlds are integral to the stories of video games, and the characters of games oftentimes relate to the game’s world in different ways. If the characters have different stakes in the world, then the relations between those stakes, along with the weight given to each of those stakes, must be mindfully architected, or else the whole narrative could be thrown out of balance. And, although we might think it obvious, FFXIII-2 shows us how crucial it is that the principal avatar in a game is actually invested in the world of that game. After all, what incentive does a player have to act as an avatar that does not wish to participate in the game’s world?

But, with that, a new chapter is beginning. Here’s hoping that Square learned from its mistakes, and that Final Fantasy XV has a story worth telling. The only way to know for sure is to dive into its world and find out. Or, you could head back here in a few weeks and see what I think of it.

Or both. Both is good.

Laila will be exploring how horror storytelling in video games fits into broader, long-standing traditions of horror in folklore, mythology, and literature. What does BioShock have to do with the Odyssey? How does Lovecraftian horror come about in S.O.M.A.? What insight can a Minotaur give us into Amnesia? Laila has answers to all of these questions–oh, and she’ll be talking about “daemonic warped spaces” and P.T., too.

Laila will be exploring how horror storytelling in video games fits into broader, long-standing traditions of horror in folklore, mythology, and literature. What does BioShock have to do with the Odyssey? How does Lovecraftian horror come about in S.O.M.A.? What insight can a Minotaur give us into Amnesia? Laila has answers to all of these questions–oh, and she’ll be talking about “daemonic warped spaces” and P.T., too.